The Changes: Part 2

Normalcy is a funny thing. Think of every room you've ever been in and questioned at some point your very reason for being there. Everything feels as it should, dust laid to rest in all the right places. As the hours of the day wither, you come to realize just how typical and familiar it all feels, and comfortable because of it. Whether it's your job, conversations you have, or the every day things you do, the knife of routine gets embedded so deeply that you lose the power to distinguish the handle from the blade, leading to the arrival of a new reality you involuntarily accept, though anticipate nonetheless.

On November 4th 2015, my son Joseph underwent his final chemotherapy treatment. Occasional breaks and work meetings aside, every Wednesday for 48 weeks was spent at the Bass Center at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital in Palo Alto. On the mound of each week, time would drop like an anchor, only one designed to inspire motion, to steer away from something unthinkable though what began to feel surprisingly ordinary. Following our son's first post-treatment scans, it felt like we were reintroduced to the world, one reality left behind as another stood by to welcome us. And like wild animals released from captivity, we were unsure of what to expect.

The days would usually start like any other. My sons and I would wake up around 7:00 a.m., sometimes 8:00 if I pushed it. I would feed them breakfast and put on an episode of Sesame Street (always the go to). While they ate, I would check the news, Facebook, and before the film’s release, watch the trailers for The Force Awakens repeatedly. After dropping Sammy off at my wife's parents' house, Joseph and I would make the trek to Palo Alto through a seemingly time sucking portal. In the room, Joseph would sit in his stroller as Finding Nemo or Toy Story played on the small television, while his insides were doused with medicine. Despite his young age, he would usually remain still, almost unabashed, and take it with little to no issue. He created bonds with the nurses, one in particular, Gailene, whom he would damn near rip himself from his stroller to hug.

He was known as the "easy one" among the staff due to his calm and playful demeanor. Whether they were accessing the port in his chest for labs, or preparing to administer the chemo itself, he always seemed happy to be there. He would watch his movie, deliver a smile to anyone who entered the room, walk around a bit (when he learned to walk) and we would leave. This was our routine. And it was one I couldn't help but think I would be sad to depart as we prepared for a new chapter in our lives. This was a moment shared between my son and I. And we shared it every week. I became the figure he sought when he felt scared or emotional, the parental brick, although out of shape, he could lean on. He was too young to understand what was happening to him and why we made these weekly trips. For all he knew, this was a totally awesome theme park that traded lines for waiting rooms, rides for movies, comfort for health.

When his last treatment day arrived, the emotions I had always expected to surface were almost non-existent. I was flooded with relief but felt barricaded by the idea that I would somehow miss this place, these people. I would no longer be required to make the drive each week, or have to subject one of my days off to these appointments, hindering plans that would normally include our then three-year-old, Sammy. The routine was slowly coming to an end. And I wasn't prepared for it. I liked spending this time with my son. I may never understand it. It feels almost demented now. Normalcy is what it eventually introduced, and as curious as it sounds, was strangely comforting. No illusions are had, mind you. I know my outlook would be very different had this turned out another way, had he not responded so well to the treatments or was diagnosed with a more severe form of cancer. I don't give a shit about luck because I'm not convinced that that played any kind of role in our situation. We survived the year, as did he, and that was good enough for us.

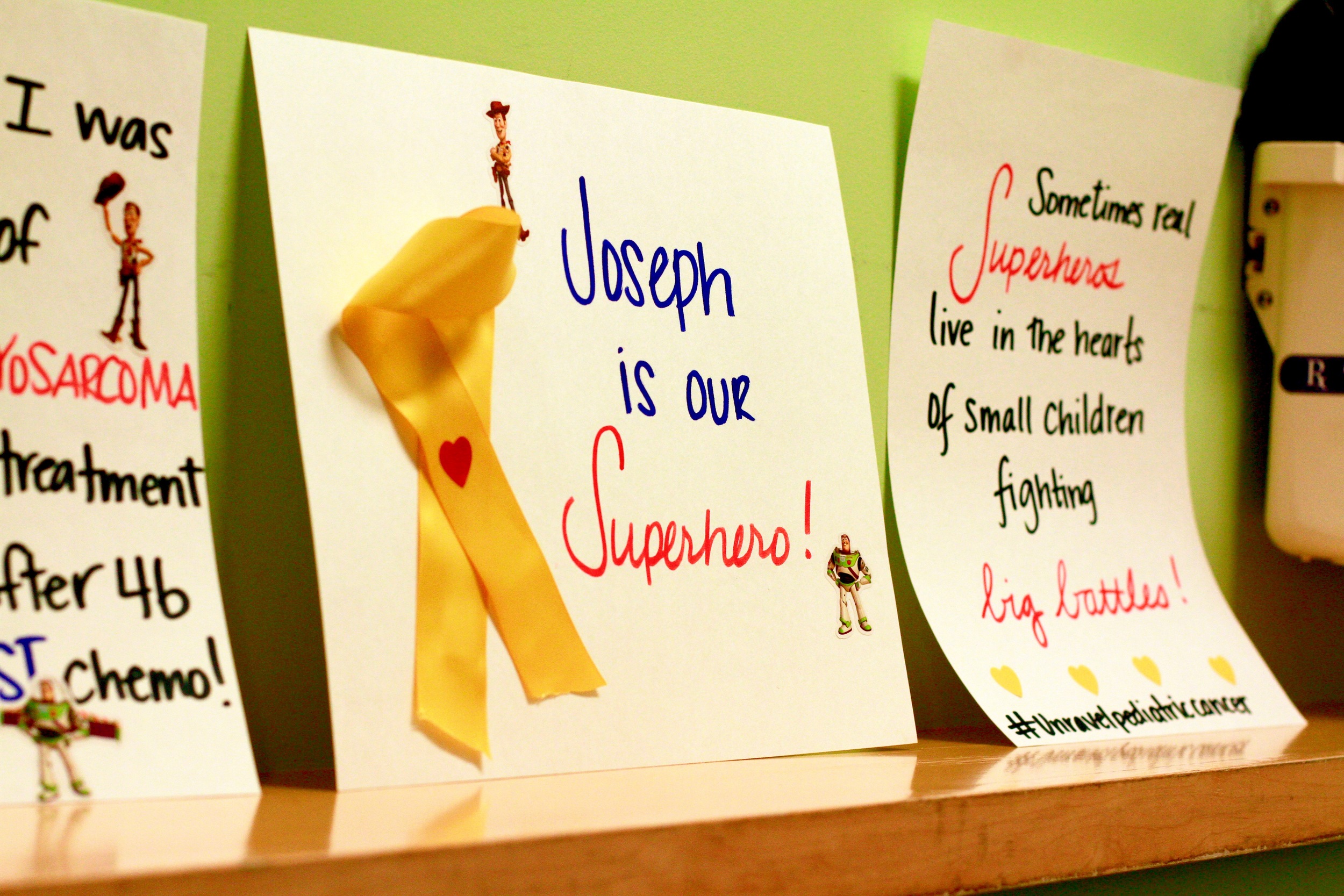

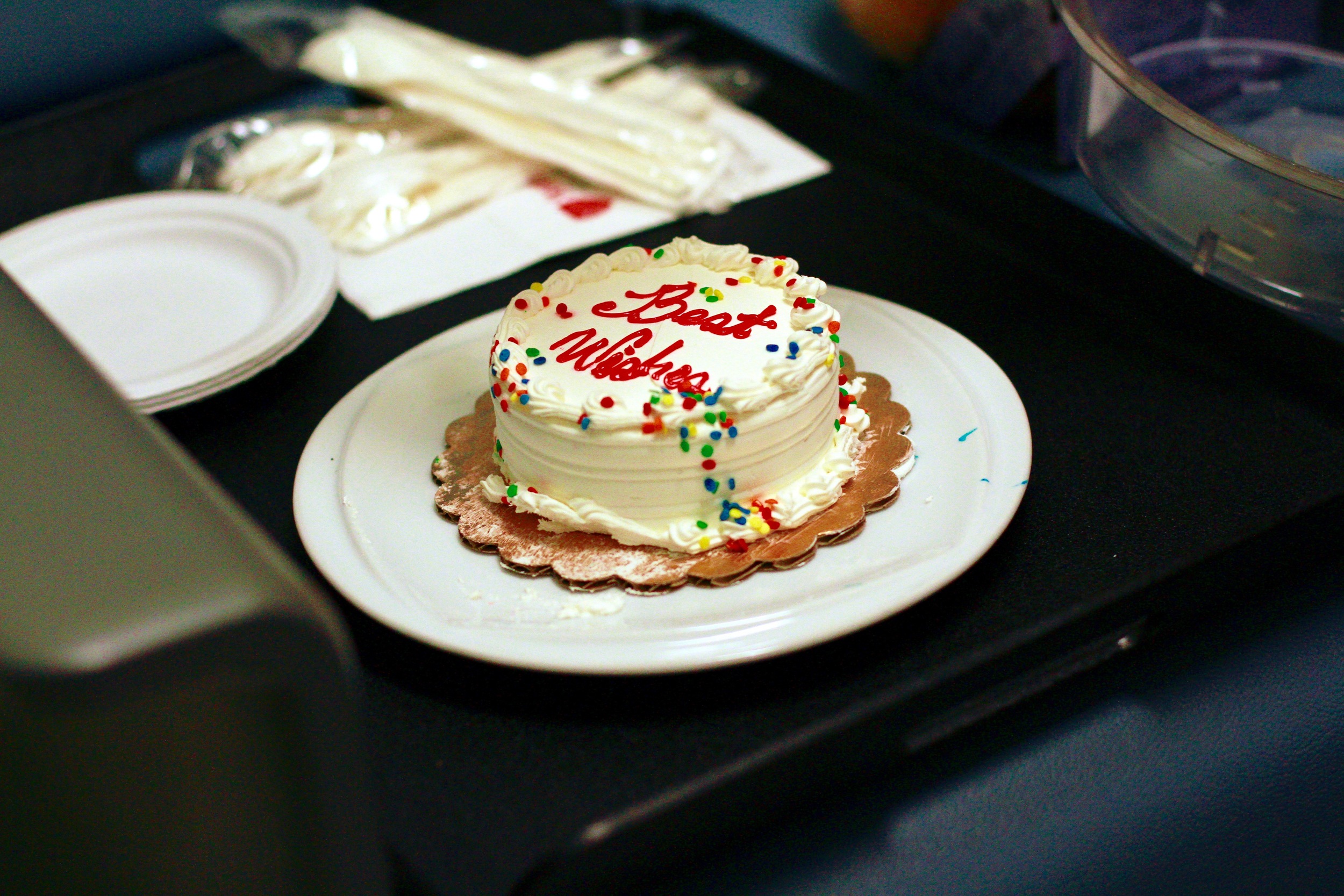

The following collection of images were taken on his last day. My wife Josephine made posters to honor the event and the staff of the Bass Center made a cake for him which was ushered in by a team of nurses who sang an end-of-therapy song to him. The gesture was heartwarming and is something my wife and I will never forget. This entire year has been comprised of moments I felt not only strengthened our marriage but my own understanding of the concept of family values and what it means to be a father. These ideas were never lost on me but having to witness my son go through what he did is something I hope I'll never have to relive, though in some weird way, am glad I did. We were there for our son and aided him throughout this entire ordeal. The pages haven't been ripped out of the story. They were bookmarked, memories on which we'll reflect when faced with hurdles we are sure to see in the future, with anything, with life. It's not a manual. It's simply a notebook of experiences.

As I write this, I am overcome by the amount of support we've received from our family and friends, the unspoken words having been just as meaningful. It's not easy to ask a parent how their sick child is coping. I understand this completely. Fortunately for us, the answer was always positive. The images to which I was preview of some of the patients in the waiting room will stay with me for good. There are struggles out there that I can't even pretend to fathom. I wouldn't want to. But I know our membership in that particular group has yet to expire. That's a fear that remains current. Dormant, but very much alive. Over the next few years, Joseph will need to be brought in for quarterly scans to review his condition and ensure there isn't a group of cells hiding behind a wall, in a trashcan, or under a lamp shade somewhere in his body. We hope we've seen the last of it. In Part 1 of this blog, I wrote of a shadow I knew would always be with us. It doesn't matter though. Because so will our son.